It gives me pleasure to report that they answered every expectation. In many respects their conduct was heroic. No troops could be more determined or more daring...”

– General Nathaniel P. Banks

The Heritage Monument is a landmark monument that only begins to recognize all that African Americans have sacrificed for our country, despite the fact that American history has not long been kind to our Black veterans. Going back to the Civil War (1861-1865), Black soldiers fought bravely to defend our nation’s values of freedom and equality. One such battle, the Siege at Port Hudson, was the first time formerly enslaved Blacks were allowed to see combat in the United States Army. Their brave service and sacrifice paved the way for other African Americans, men and women, to serve in all branches of the U.S. military from the battlefields to the highest ranks.

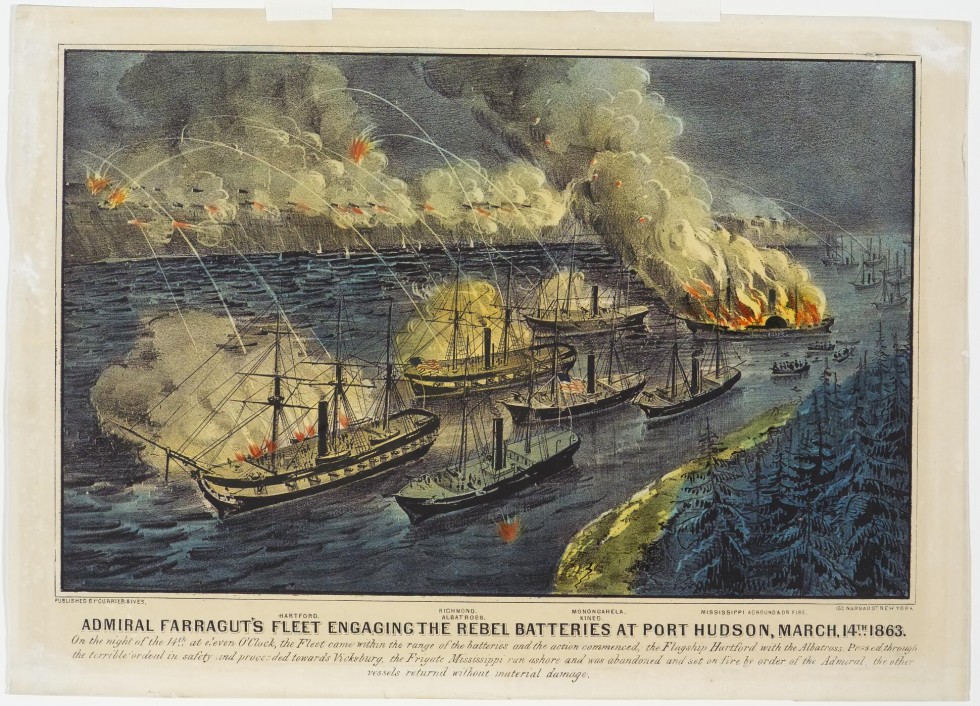

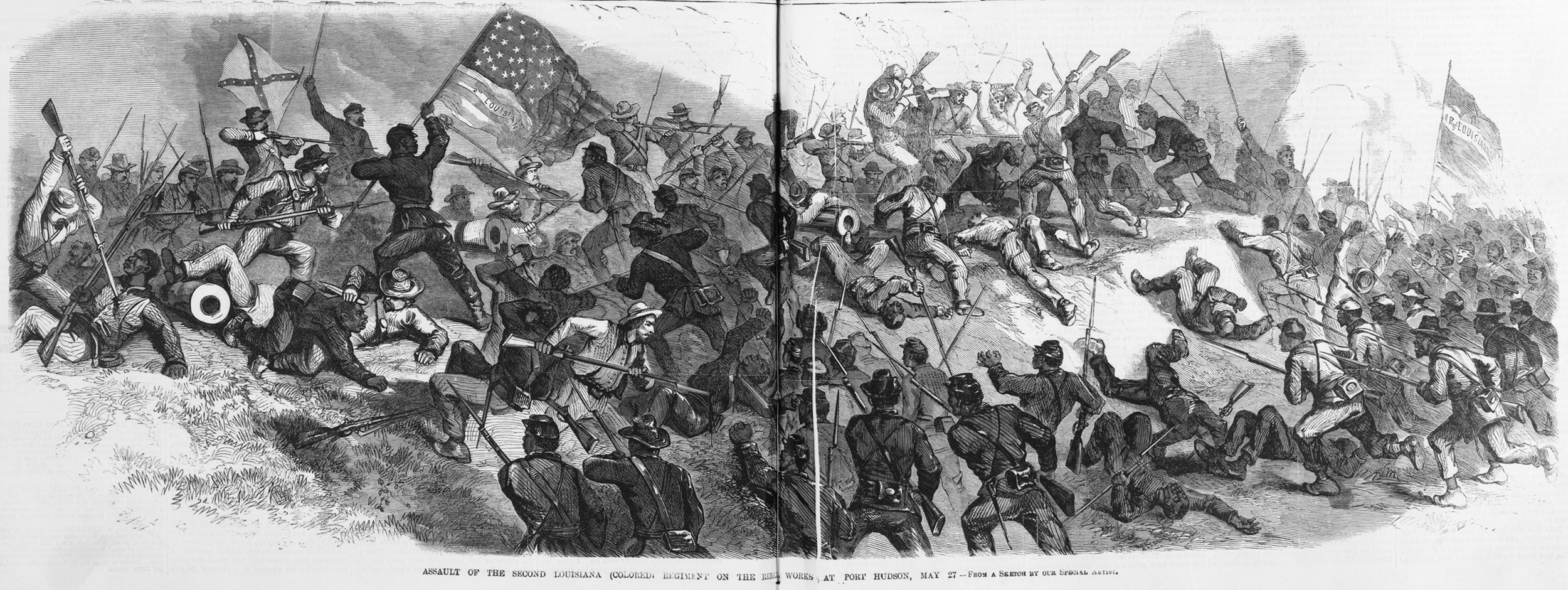

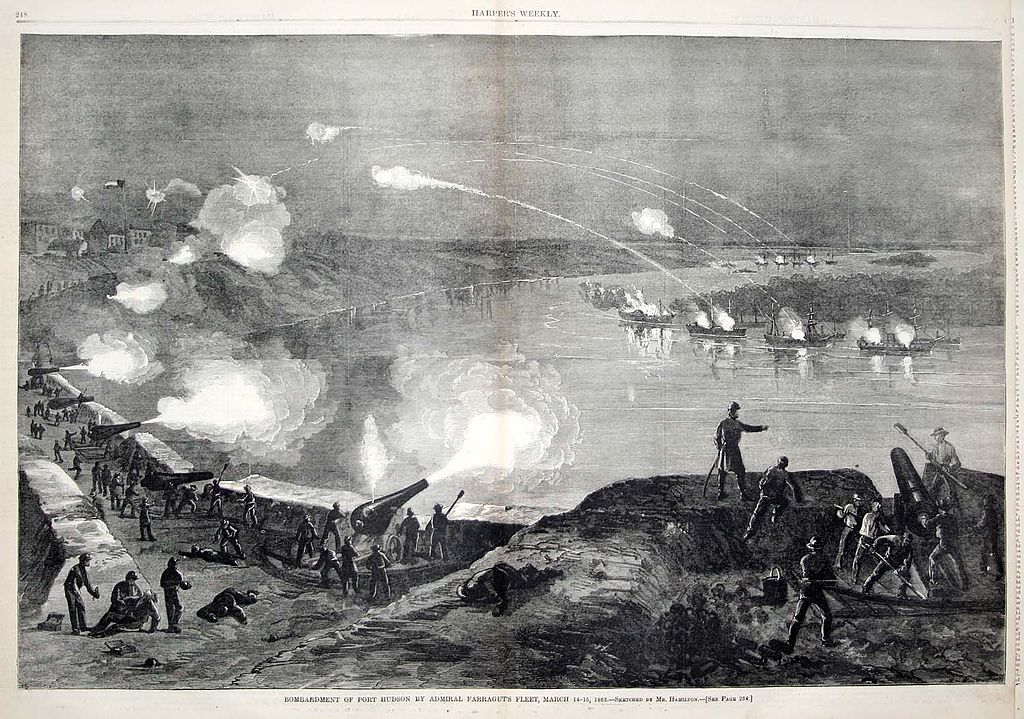

On May 27, 1863, hundreds of black soldiers, part of the 1st and 3rd Louisiana Native Guard Infantry regiments in the Union army, bravely stormed Port Hudson, one of the last Mississippi River strongholds held by the Confederate army. That particular assault, led by General Banks, was unsuccessful, leaving hundreds dead and more wounded. However, as the following excerpts from various historians describe, even the Union army treated the African American soldiers as second class despite all having put their lives in danger and some having made the ultimate sacrifice. The Native Guards were primarily raised from Louisianans, and Black soldiers even had the unique opportunity to serve as company commanders. These sacrifices made by the 1st and 3rd regiments of the Louisiana Native Guards in 1863 inspired the Heritage Monument and its recognition of the Native Guards’ work and the Black soldiers who would soon, and for years to come, follow in their footsteps.

During the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863, which freed enslaved people within seceded territory. Benjamin Butler, a Union general, designated fugitive slaves who penetrated unit lines as contraband to avoid the requirements of fugitive slave laws at the time, and once black soldiers joined the military, they were not allowed to see combat. All of this changed at the dawn of the Port Hudson assault. The Native Guards met their challenge bravely, as historian Anthony Cade explained in a bio published by the Society for Military History:

During the American Civil War, the largest group of African Americans to serve in the Union Army were raised in Louisiana. The majority of these men served within a series of regiments first designated the Louisiana Native Guards and later redesignated the Corps d’Afrique before being split into multiple USCT regiments. The regiments these men served in were first constituted by the Confederacy as a militia unit, and then after the Union regained control of New Orleans, was absorbed by the Union Army into the Department of the Gulf. Their contribution to the war was possibly the most significant act of any regiment raised in the South, and their actions directly changed African American society in New Orleans, and all of Louisiana, during and after the Civil War. Furthermore, their actions ensnared enough international attention, that they made the war in Louisiana a transnational war.[1]

While the 2nd regiment of the Native Guards did not fight in the Port Hudson siege, their brave service was engaged in other Civil War skirmishes, including the first confrontation of Confederate troops on the Gulf Frontier while the 2nd regiment was stationed at Ship Island. Others took up station at Fort Pike, Louisiana.[2]

The historic battle of Port Hudson was dynamic and challenging. Renowned Civil War historian Shelby Foote offered some description in The Civil War: A Narrative, Fredericksburg to Meridian (1963):

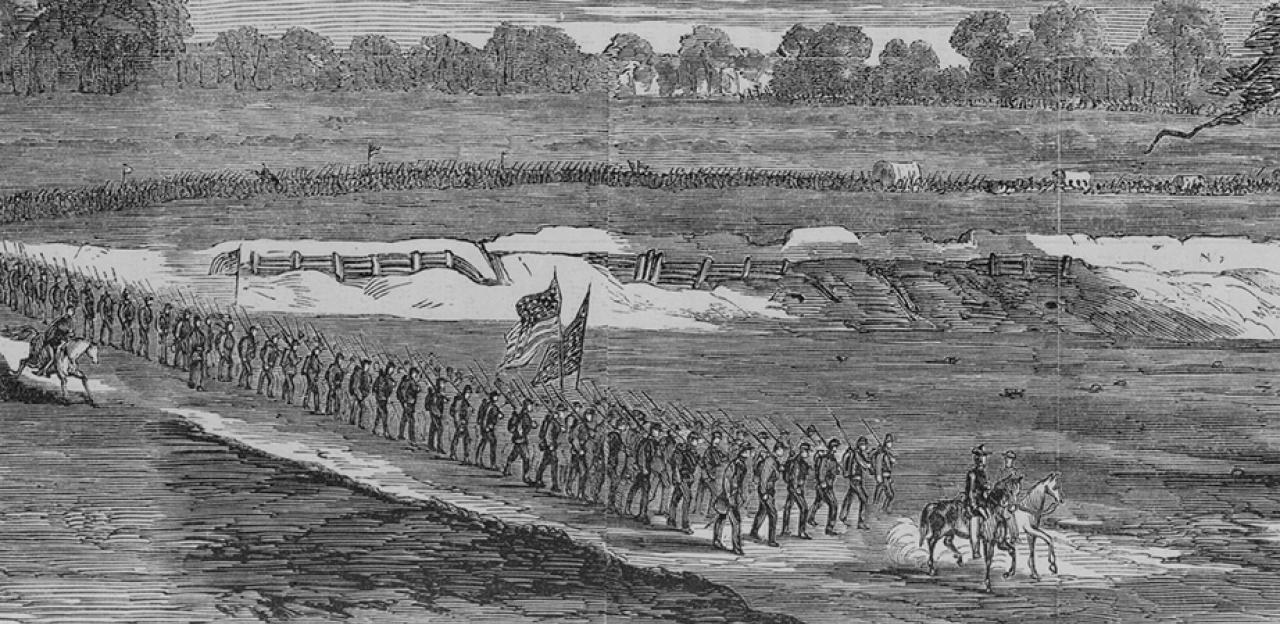

...Back in New Orleans the year before, Ben Butler had begun to enlist freedmen and fugitive slaves in what he called his Corps d’Afrique; now Banks continued this recruitment in the Teche. Two such regiments were organized at Opelousas, with about 500 men each. Styles the 1st and 3rd Louisiana Native Guards, the former was composed of ‘free Negroes of means and intelligence,’ with colored line officers and a white lieutenant colonel in command, while the latter was made up largely of ex-slaves whose officers were all white. There was considerable speculation, in the army of which they were now a part, as to how they would behave in combat – when and if they were exposed to it, which many of their fellow soldiers thought inadvisable – but Banks was willing to abide the issue until it had been settled incontrovertibly under fire...

...Orders were sent to the far right for a resumption of the assault, and were passed along to the colonel commanding the two regiments lately recruited in the Teche, the 1st and 3rd Louisiana Native Guards. Held in reserve until now, they were about to receive their baptism of fire: a baptism which, as it turned out, amounted to total immersion. A Union staff officer who watched them form for the attack described what happened. “They had hardly done so,” he said, “when the extreme left of the Confederate line opened on them, in an exposed position, with artillery and musketry and forced them to abandon the attempt with great loss.” However, that was only part of the story. Of the 1080 men in ranks, 271 were hit, or one out of every four. They had accomplished little except to prove, with a series of disjointed rushes and repulses over broken ground and through a tangle of obstructions, that the rebel position could not be carried in this fashion. And yet they had settled one other matter effectively: the question of whether Negroes would stand up under fire and take their losses as well as white men. “It gives me pleasure to report that they answered every expectation.” Banks wrote Halleck. “In many respects their conduct was heroic. No troops could be more determined or more daring.”[3]

|

André Cailloux |

One famous commander in the Native Guard units at Port Hudson was named André Cailloux, a Black Frenchman from New Orleans. He played a valiant role as he led his men through the difficult conditions of battle. From historian Stephen J. Ochs, A Black Patriot and a White Priest: André Cailloux and Claude Paschal Maistre in Civil War New Orleans (2000): |

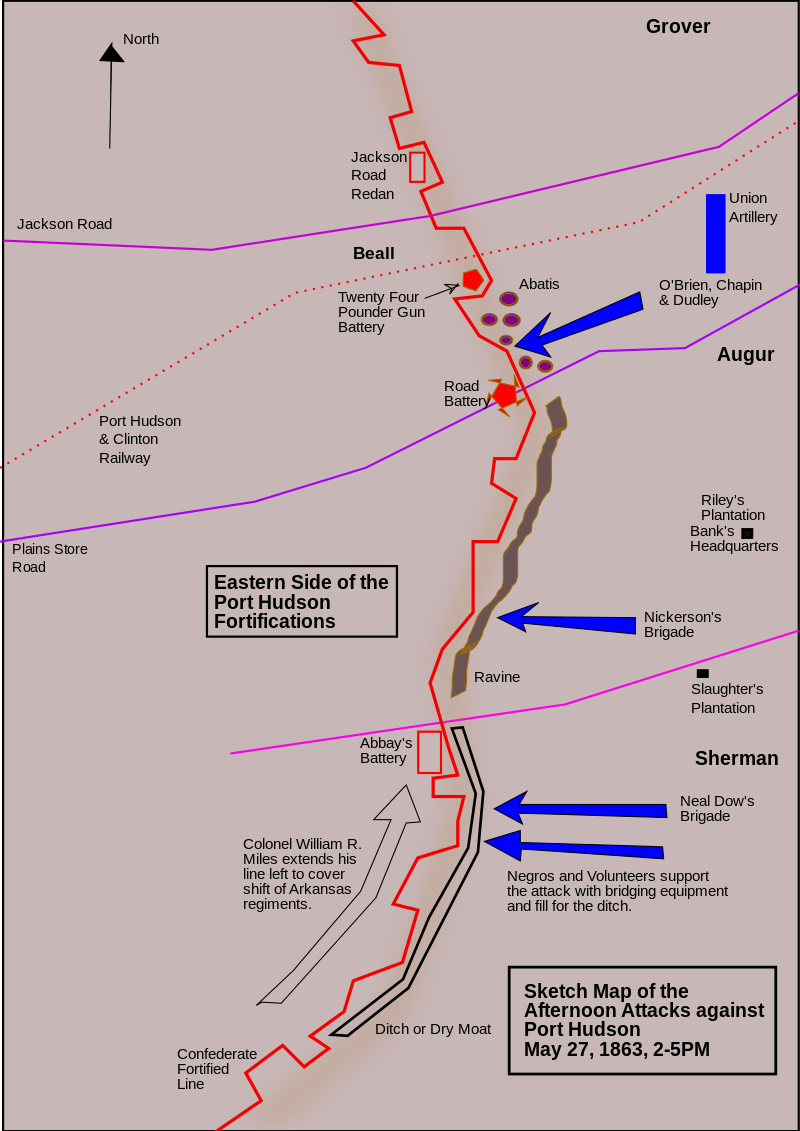

What they saw as they came to the edge of the woods must have startled them, for they did not gaze on the ‘smooth’ approach to Port Hudson that Dwight had promised them. Instead, several hundred yards in front of them, running parallel to a road they had to cross, stood a rugged bluff about four hundred yards in length, occupied by six companies of the 39th Mississippi under Colonel W. B. Shelby. To the front, and at a lower elevation, stood a second bluff that projected boldly from the main height with a sharp return to the right to form the natural outcrop that would allow flanking fire from the rifle pits that covered it, especially in the direction of any force emerging from the road and attempting to cross the pontoon bridge over Foster’s Creek. Sixty men under Lieutenant T. C. Rhodes occupied this stronghold. A Confederate-engineered backwater from the Mississippi further protected the bluffs by forming a moat about two hundred yards in front of them. Cailloux and his men could not flank these obstacles because to the right along the road lay an impassable swamp of cottonwoods, willows, and cypress trees that ran down to the river, and to the left lay a tangled abatis of felled trees, underbrush, and gullies. To even reach the backwater, Cailloux would have to lead his men across a shallow gorge exposed to enemy gunfire and artillery. Moreover, the troops would not enjoy the artillery support promised to them; Confederate gunners had already routed the two Union batteries, with one of the latter getting off only a solitary round in return.

At 10AM, the 1st Regiment, followed closely by the 3rd, emerged from the willow forest in good order, each regiment forming a long line two ranks deep. The men advanced first at quick and then double-quick time toward the bluff about six hundred yards away. A party of skirmishers, concealed in a little copse on the attackers’ left flank, fired on them, while to their front they faced a volley from the rifle pits and the simultaneous discharge of artillery. The barrage threw the leading elements into confusion, and they broke and ran to cover among the willows. Cailloux and other officers rallied their men using swords, threats, curses, and words of encouragement. Accounts differ as to how many times the men reformed, charged, broke, and reformed again. Some way once, some three, some as many as six times. Cailloux led a charge of screaming and shouting men that reached the backwater, about two hundred yards from the bluffs. At that point, they fired their first and apparently only volley. In response, Confederate artillery opened up on them with a solid shot, grapeshot, and canister and the infantry rained down lead. Only the availability of trees, stumps, and other obstacles prevented a complete slaughter. As one member of the regiment recalled, “Quite a number of men were hurt in that fight by the limbs of trees falling on them.” One of these was Frank Trepagnier, who remembered, “A shell from a rebel battery cut the limb of a tree and it fell on me injuring my back. It struck me across the small of the back, knocked me down and I was carried off the field.” One Confederate veteran of the battle who was positioned directly opposite the charge of the black troops recalled, “They were fighting in the timber and suffered severe bombardment and sustained several desperate charges. We ran them back on the white troops that were supporting them several times.” John A. Kennedy of the 1st Arkansas Regiment watched the black soldiers move toward the moat but, refusing to attribute bravery to them, less generously explained their willingness to make the charge to Yankee troops positioned behind them, allegedly forcing them to fight.

Even in the midst of the pandemonium that had broken loose, Cailloux remained true to the code of “sublime courage” that dictated that officers “lead the charge” and boldly place themselves in danger to demonstrate their valor and to embolden and rally their men. His face ashen from the sulfurous smoke, his left arm dangling by his side – broken by a ball above the elbow – while his right hand held his unsheathed sword, Cailloux hoarsely exhorted to his soldiers: “En avant, mes enfants!” (Once more, my children) and “Follow me!” His color company presented an especially good target for rebel sharpshooters. As Cailloux moved in advance of his troops urging them to follow him across the flooded ditch, he was killed by a shell that struck him in the head. Sergeant Planciancios, boldly and conspicuously flourishing the flag, was also felled by a missile that cut the banner in two and carried away part of his skull. Two men nearby struggled to raise the brain-splattered standard: one of them, the recently promoted eighteen-year-old corporal Louis Leveiller, fell mortally wounded. The other, Athanase Ulgere, a former slave, took a bullet in his left hand as he retrieved the colors.[4]

Once the battle concluded, it was not simply finished. The Union army brutally lost their challenge and although they would not yet give up, there was an egregious mishandling of the casualties from the May 27th skirmish. From historian Stephen J. Ochs, A Black Patriot and a White Priest: Andre Cailloux and Claude Paschal Maistre in Civil War New Orleans (2000):

...as a New York Times correspondent noted, “In the midst of the carnage, when men in every form of horrible mutilation were being sent to the rear... - after fighting as few white men could have fought – not a single ambulance or stretcher was there to gather their torn and incapacitated bodies.” Nor, parenthetically, was a priest present to tend to their spiritual needs. Banks’ assault on Port Hudson had completely failed in all sectors. The Union had suffered a total of 1,995 casualties, and Banks had lost the respect and confidence of his men; the Confederates had a total of 235 killed, missing, and wounded.

That night, some of the Confederate troops left their lines to search the dead and dying who lay in front of them. They first encountered the body of Cailloux, which lay in advance of the others near the ditch. Some native New Orleanians recognized him. In his pocket, they found his officer’s commission and eight dollars in greenbacks. During a four-hour truce the day after the assault, Union details retrieved and buried the remains of all the white soldiers. Cailloux and other Louisiana Native Guards, however, were left to lie where they had fallen. Walter Stephens Turner of the 39th Mississippi Infantry wrote in his diary on the 28th, “The enemy have buried all their white men and left the Negroes to melt in the sun. That shows how much they care for the poor ignorant creatures. After they are killed fighting in their battles, having done all they can for the Federals then for them to let the bodies of the poor creatures lie and melt in their own blood and to be made the prey of both birds and beasts.” [5]

From historian Joseph Glatthaar in the Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association 35, no. 2 (spring 1994):

What was so unusual about the Louisiana Native Guards was that not only the enlisted men but also the company-grade officers were black, as was one field officer, the wealthy slaveholder Francis Dumas. These officers came predominantly from the free black population of New Orleans, noted for its education, wealth, and tradition of military service, and Butler had no problem obtaining men with leadership skills. Because he appointed officers “precisely as I found intelligence,” some seventy-five blacks received commissions as captains and lieutenants and Dumas as major. All other field officer posts Butler reserved for experienced white soldiers.

This great achievement for blacks, however, was short-lived. In December 1862 the War Department replaced Butler with Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks, a former governor of Massachusetts and an opponent of the concept of black officers. Banks, convinced that blacks lacked the character necessary for effective command, and that black officers reduced the effectiveness of his army by creating excessive racial tension, began the systematic removal of black officers by any means available. Even the exceptional performance of black officers in combat on two occasions, one being the battle of Port Hudson, the first major engagement in which black soldiers participated, failed to dissuade Banks from his purge. By the summer of 1864, the pressure and abuse was so intense that the last of the black officers succumbed and resigned.[6]

The impact of the Black soldiers who so valiantly fought during the Siege at Port Hudson on our nation should always be remembered. Their bravery and sacrifice created the pathway for all other Black soldiers who have followed in their footsteps and served in every branch of the military. Sadly, many of these military heroes who dedicated their lives to protecting our country were not treated with the respect and equality they so deeply deserved upon returning home simply because of the color of their skin. The Heritage Monument is a recognition of their service and sacrifice. While it is long overdue, it will hopefully be part of ongoing efforts to correct that injustice and inspire everyone to learn more about their contributions that are too many to count and too significant to ever forget.

They struggled and fought, with courage fraught,

With love for the cause of the Nation;

They knew in the strife for the Union’s life

They must buy Emancipation[7]

- George Washington Williams

A History of the Negro Troops in the War of the Rebellion 1861-1865

Bibliography

Foote, Shelby. The Civil War: A Narrative, Fredericksburg to Meridian. New York: Random House, 1963.

Glatthaar, Joseph. “The Civil War through the Eyes of a Sixteen-Year-Old Black Officer: The Letters of Lieutenant John H. Crowder of the 1st Louisiana Native Guards,” Louisiana History: Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association 35, no. 2 (Spring 1994), 201-216.

Ochs, Stephen J. A Black Patriot and a White Priest: Andre Cailloux and Claude Paschal Maistre in Civil War New Orleans. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2000.

_________________________

[1] “Second Native Guard,” Gulf Islands National Seashore, National Park Service, last accessed 18 July 2023; https://www.nps.gov/articles/2la-guard.htm#:~:text=The%20soldiers%20of%20the%202nd,and%20officers%20on%20Ship%20Island.

[2] “Anthony Cade,” Society for Military History, updated 27 May 2023, last accessed 18 July 2023; https://www.smh-hq.org/grad/gradbio/anthonycade.html.

[3] Shelby Foote, “The Beleaguered City: The Vicksburg Campaign, December 1862-July 1863,” in Civil War, A Narrative, Volume 2 (New York: Vintage Books, Random House, 1963), beginning page 323.

[4] Stephen J. Ochs, A Black Patriot and a White Priest: Andre Cailloux and Claude Paschal Maistre in Civil War (New Orleans. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2000), 142-144.

[5] Ochs, Black Patriot, 147-148.

[6] Joseph Glatthaar, “The Civil War through the Eyes of a Sixteen-Year-Old Black Officer: The Letters of Lieutenant John H. Crowder of the 1st Louisiana Native Guards,” Louisiana History: Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association 35, no. 2 (Spring 1994), 202.

[7] George Washington Williams, “The Negro Volunteer,” in A History of the Negro Troops in the War of the Rebellion, 1861-1865, 341.